From a mechanism for deferred payment, to a store of value and then a medium of exchange. Stablecoins? We’ve been here before, as I explained to our guest at Money20/20 in Amsterdam this year.

Dave Birch

Global Ambassador, Consult Hyperion x FimeA ledger technology, a means for recording transactions, needs to be fit for purpose. It needs to be cost-effective, convenient, appropriate for its users, immutable (of course), long lasting and so on. We’ve been here before, by the way, with the tally sticks. To begin at the beginning, then, what are tally sticks? Well, here is an article I wrote about them for the Financial Times Virtual Finance Report almost three decades ago (FTVFR, Vol. III, No. 5, May 1998)…

Tally Ho!

Tally sticks came into use in England after the notorious war criminal William the Bastard’s illegal invasion and regime change of 1066. Tax assessments were made for areas of the country and the relevant sheriff was required to collect the taxes and remit them to the crown. To ensure that both the sheriff and the king knew where they stood, the tax assessment was recorded by cutting notches in a wooden twig and then splitting the twig in two, so that each of them had a durable record of the assessment. When it was time to pay up, the sheriff would show up with the cash and his half of the tally to be reckoned against the King’s half. As the system evolved, the taxes were paid in two stages: half paid up front at Easter and the rest paid later in the year at Michaelmas when the “tallying up” took place.

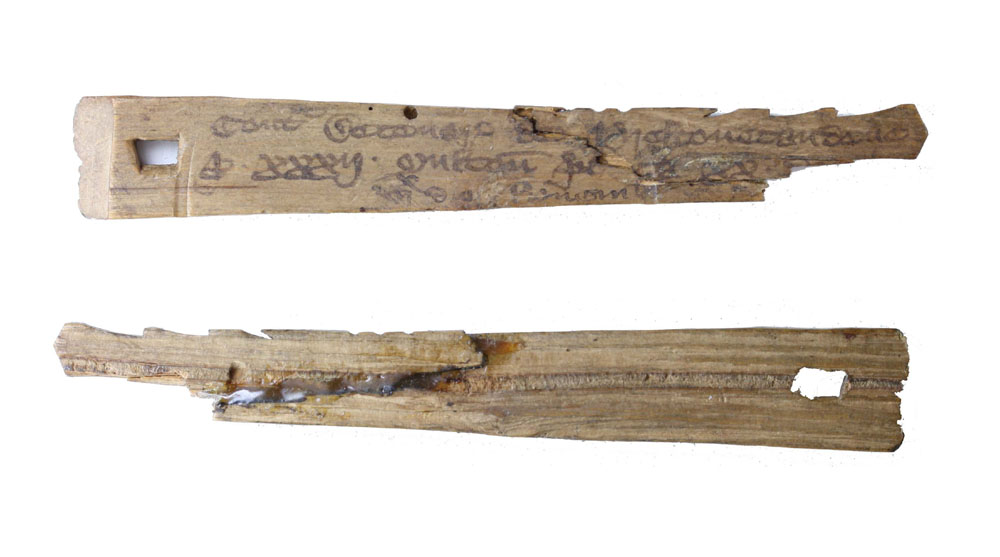

Medieval English split tally stick (front and reverse view). The stick is notched and inscribed to record a debt owed to the rural dean of Preston Candover, Hampshire, of a tithe of 20d each on 32 sheep, amounting to a total sum of £2 13s. 4d.

The technology worked well. The tally sticks were small and long–lasting (after all, they still exist, you can go and see some in the British Museum), were easy to store and transport, and easily understood by those who couldn’t read (which was almost everyone).

As a new technology, however, they soon began to exhibit some unforeseen (in the context of their record–keeping function) characteristics. During the extended period of use of any technology, creative people come along and find new ways to use the technology in different times, in different cultural contexts. Tally sticks were a form of distributed ledger to record debt, and were soon being used as money.

From Deferred Payment to Store of Value.

By the reign of Henry II (who died in France in 1189), the Exchequer was already a sophisticated and organised department of the king’s court with an elaborate staff of officers. The use of tallies to enable this operation had an interesting consequence. Since the king (as is generally the case) couldn’t be bothered to wait until taxes fell due, and could not borrow money at interest, he would sell the tallies at a discount. The holder of the tally could then cash it in when the taxes fell due, making it (in effect) a fixed–term government bond. Since paying interest was forbidden by the church, selling tallies at a discount became a key means for the Crown to borrow money without God noticing what was going on.

The discount on the tallies, being equivalent to the interest rate for government debt, varied just as one would expect. As economic circumstances changed, so did the discount rate. Adam Smith noted that in the time of King William the discount reached 60% when the Bank of England suspended transactions during a debasement of the coinage. Clearly, then, the tally system could be (and was) abused by the Exchequer selling tallies which they would not redeem, but the Crown soon learned not to renege on tallies, since the discount on future tallies would be increased and the Exchequer would be hit hard.

To summarise: by middle of the twelfth century, there was a functional market in government debt centred on London. No wonder the London money markets are so sophisticated. I often fall into the trap of thinking that there’s never been a revolution in monetary technology before, so I forget how rapidly previous significant developments were co–opted by the financial ‘establishment’ and taken for granted or just how old some aspects of the apparently modern financial infrastructure are.

From Store of Value to Means of Exchange.

The market for tallies evolved quickly. Someone in (say) Bristol who was holding a tally for taxes due in (say) York would either have to travel to collect their due payment or find someone else who would, for an appropriate discount, buy the tally. Thus, a market for tallies grew, arbitrating various temporal and spatial preferences by price. It is known from recorded instances that officials working in the Exchequer helped this market to operate smoothly. The distributed ledger technology of the tally had been used to convert a means for deferred payment into a store of value and then into a means of exchange, and the sticks remained in widespread use or hundreds of years.

The Bank of England, being a sensible and conservative institution naturally suspicious of new technologies, continued to use wooden tally sticks until 1826: some 500 years after the invention of double–entry bookkeeping and 400 years after Johann Gutenburg’s invention of printing. At this time, the Bank came up with a wonderful British compromise: they would switch to paper, but would keep the tallies as a backup (who knew whether the whole “printing” thing would work out, after all) until the last person who knew how to use them had died!

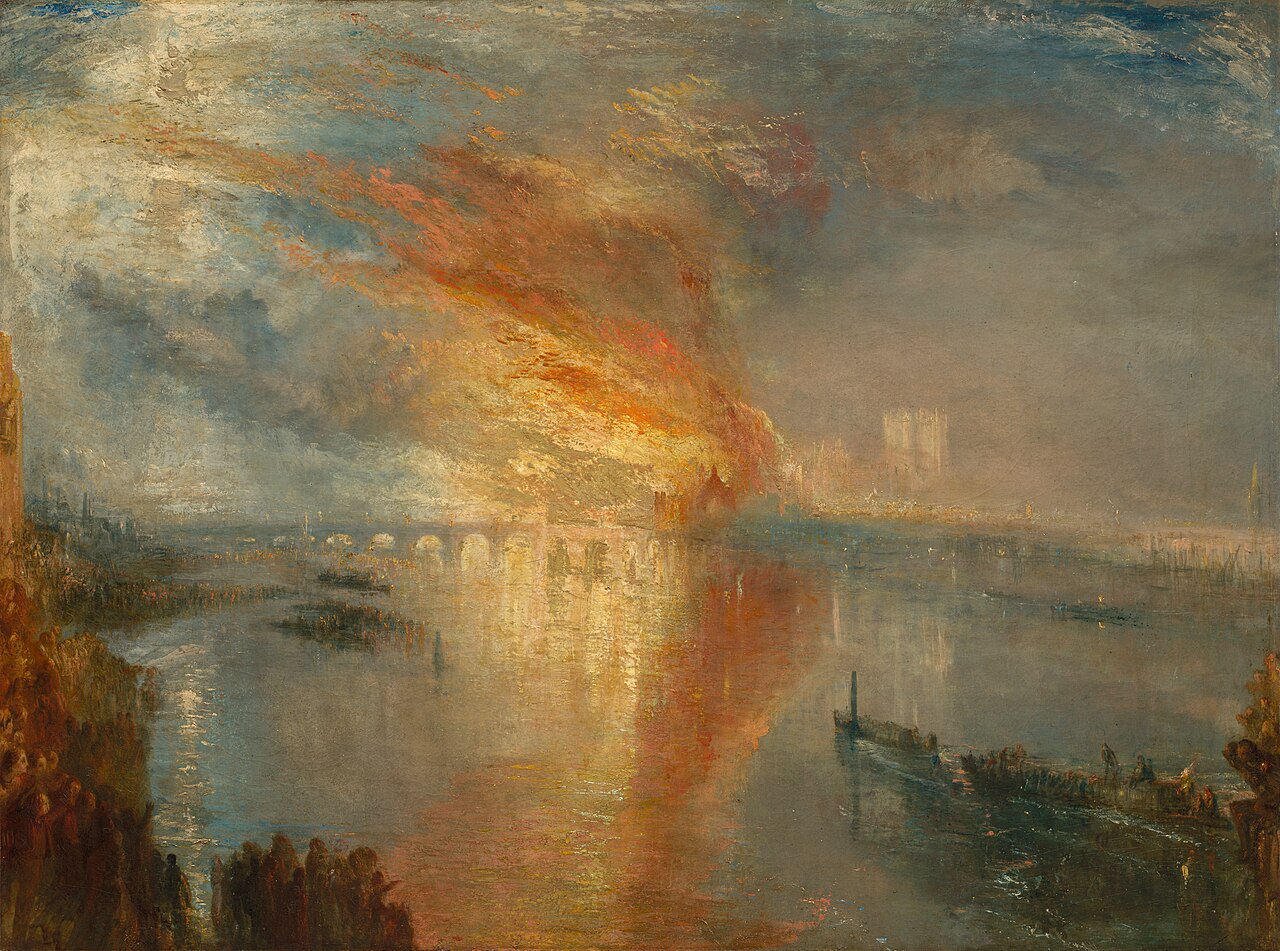

Thus, tally sticks were then taken out of circulation and stored in the Houses of Parliament until 1834, when the authorities decided that the tallies were no longer required and that they should be burned. As it happened, they were burned rather too enthusiastically and in the resulting conflagration the Houses of Parliament were razed to the ground, which is why they are now a Victorian gothic pile rather than a medieval palace, in an incident so loaded with symbolism about the long–term impact of innovations in the technology of money that had it occurred in a novel no–one would believe it.

The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons is the title of two oil on canvas paintings by J. M. W. Turner, depicting the fire that broke out at the Houses of Parliament on the evening of 16 October 1834. Turner himself witnessed the burning of Parliament from the south bank of the River Thames, opposite Westminster.

Stable.

The tally sticks, just like USDC, were backed by government debt. Just as USDC is backed by US Treasury Bills, so the tally sticks were backed by the tax-raising power of the monarch. Nothing much has happened in a thousand years, has it!